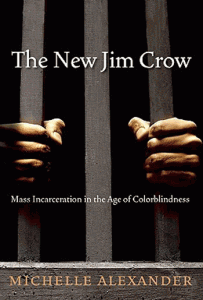

The New Jim Crow

Remedying the Harsh Realities of ‘Incarceration Nation’

by Diane Lefer

“Drug prohibition is the biggest failed policy in the history of the United States, second only to slavery.”

Maybe that was not a surprising claim to hear at the Pasadena-Foothills ACLU chapter’s public forum held at Neighborhood Church on May 10th. After all, the chapter was co-sponsor of Michelle Alexander’s appearance in March at the Pasadena Public Library where she reported, as detailed in her book The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness, that largely as an intentional consequence of the “war on drugs,” there are more African American men under correctional control now than were enslaved in 1850. What was maybe unexpected was to hear the claim from James P. Gray — a white guy from Orange County who is a retired judge, former Navy man, and a former federal prosecutor who put people away after major drug busts.

Maybe that was not a surprising claim to hear at the Pasadena-Foothills ACLU chapter’s public forum held at Neighborhood Church on May 10th. After all, the chapter was co-sponsor of Michelle Alexander’s appearance in March at the Pasadena Public Library where she reported, as detailed in her book The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness, that largely as an intentional consequence of the “war on drugs,” there are more African American men under correctional control now than were enslaved in 1850. What was maybe unexpected was to hear the claim from James P. Gray — a white guy from Orange County who is a retired judge, former Navy man, and a former federal prosecutor who put people away after major drug busts.

Gray was a featured speaker, along with Pasadena police chief Phillip Sanchez and public defender Shelan Joseph. Each brought a distinct perspective to address how to respond to the mass incarceration of men (and women) of color.

The United States today locks up more of its citizens than any other country. Pew Center surveys concluded that one in every 100 Americans now lives behind bars. Alexander reported on people of color rounded up en masse for relatively minor, non-violent drug offenses. In 2005, for example, four out of five drug arrests were for possession. She has written that most people in state prison have no history of violence or even of significant selling activity and that during the 1990s, nearly 80% of the increase in drug arrests was for marijuana possession. It’s easy to understand why this isn’t generally understood in middle-class white communities: As long as white college students and middle-class recreational users aren’t being busted for pot, it’s easy to assume the war on drugs targets only the violent cartels and the worst of the worst.

What does this have to do with Jim Crow? Prisoners and, in many states felons, lose the right to vote and serve on juries. Felons, upon release from prison, face legal — often mandated — discrimination in housing, employment, education, and eligibility for benefits. Their broken families and poverty perpetuate the existence of an underclass and a caste system. So we’re not in a post-racial utopia. As Michelle Alexander has reminded her readers and her audiences, even in slavery days, some exceptional African Americans attained wealth and status and power. Some even enslaved others.

How can we be so quick today to deprive our fellow Americans of freedom?

Shelan Joseph, who represents youthful offenders, said “We’re starting the incarceration cycle at a much earlier age.” She asked rhetorically, “What happened in school when you were growing up?” If you misbehaved, the school called your parents. “Now the first call goes to the police.” Nationwide, 90,000 kids are locked up and Latinos are two times as likely to be locked up as white kids; African American kids five times as likely. When it comes to kids with no prior criminal record, the racial disparity is even greater.

Coincidentally, the morning after the forum, the LA Times ran an op-ed by Father Gregory Boyle about how a young person’s criminal record can mean being sentenced to lifetime unemployment. One of the first comments to appear in response on the newspaper’s website read in part, “These are scumbags. I wish they would exterminate themselves at a faster rate in the hood.”

“Only 19% of the youth of color locked up in LA County were locked up for violent offenses,” Joseph said, which is something some members of the public clearly do not understand. In some LA neighborhoods, she said, children show levels of PTSD comparable to children during the worst of the war in Baghdad. “Trauma goes unaddressed at every level of the penal system.” These kids have problems and “schools would rather have them arrested than deal with them.” Arrest has an impact on taxpayers, too: “It costs $252,000/year to keep a youth in state prison where they are not getting an education or vocational training.”

Pasadena is trying alternatives to the early criminalization of kids. One approach is the Youth Accountability Board, based on the model of restorative rather than punitive justice. “When there’s a minor violation of the law, rather than put them in the judicial system,” Chief Sanchez said, “they meet with a mentor about good decision-making. The youth and the family receive counseling,” he explained. The department is now expanding the program to include young people who commit not just misdemeanors but some felonies. “Restorative justice provides an opportunity for the police department to invest in a young person so they can see the value of success and make better judgments.”

Kids need the right kind of mentors. (“Charles Manson was brilliant at mentoring,” commented Judge Gray.) “Our young people don’t learn one week at a time for an hour. You better know how to tweet and Facebook and text,” said Chief Sanchez. “You have to go to their world. They aren’t going to yours.” But about ten young people, calling themselves “Soldiers of Change,” did attend the meeting along with Alejandrina Flores who coordinates the city-sponsored Neighborhood Outreach Workers Program which mentors gang-impacted youth who continue their educations while working part-time doing outreach to their peers to reduce violence.

But what can the individual citizen do? Especially when, as audience members pointed out, some people and corporations make big money through the prison system, and manufacturing drug-testing kits — and products to thwart drug-testing kits, and while the prison system effectively exploits black and brown labor. Mary Sutton, program director of the Center for the Study of Political Graphics, invited audience members to check out the protest images on the laptop set up in the back of the room, and offered posters created by Californians United for a Responsible Budget (CURB) that urge reinvesting in communities instead of prisons. But as one audience member said, “We brought someone to the presidency to make a difference and that didn’t work out. How do you make a dent in this?”

Education, according to Shelan Joseph. She means funding our public education system, raising teacher salary and status and keeping class size down so that students can get individual attention. The prison industry is very aware of how lack of good education feeds the system.”They go to schools to check on second-grade reading scores,” she said. “That’s how they come up with projections on how many prisons to build.” Throughout the system — public schools, education in lockup,re-entry services, “we’re cutting costs on the backs of our youth.”

Education, according to Shelan Joseph. She means funding our public education system, raising teacher salary and status and keeping class size down so that students can get individual attention. The prison industry is very aware of how lack of good education feeds the system.”They go to schools to check on second-grade reading scores,” she said. “That’s how they come up with projections on how many prisons to build.” Throughout the system — public schools, education in lockup,re-entry services, “we’re cutting costs on the backs of our youth.”

“How do we teach our children today?”asked Chief Sanchez. “Where’s the critical analysis?” Standardized tests and computerized assessments don’t prepare kids to use good judgment or live in the real world. “There’s no scantron when you go to work.”

Joseph also means we must do a better job of educating ourselves and other voters. “You voted for these policies,” she said, referring to ballot initiatives that made it easier to criminalize youth and try them as adults, and the Three Strikes law that has resulted in life sentences for nonviolent and minor offenses. (Please see “150 Three Strikes Stories,” compiled by Families to Amend California’s Three Strikes law to learn who is being locked up and for what.) The last attempt to amend Three Strikes to impact only violent offenders failed at the ballot box. The 2012 ballot will give Californians another chance to end the most extreme injustices that have come about since the measure was first enacted.

California voters rejected Prop 19 that would have legalized and taxed marijuana sales. Chief Sanchez thinks we voted right. “We have to know how to regulate it and how to dispense it before we legalize it.” Judge Gray agreed that Prop 19 was poorly written. That’s why he’s drafting the 2012 measure himself, having already written a book laying out his ideas in A Voter’s Handbook: Effective Solutions to America’s Problems. “Right now it’s easier for kids to buy marijuana than alcohol. Dealers don’t ask for ID,” he said. “And it’s a big revenue source for juvenile gangs.” He made it clear that ending drug prohibition “doesn’t mean we condone drug abuse.” If you drive under the influence, that’s a legitimate criminal justice matter, he said. “Hold people accountable for their actions, not for what they put into their bodies.”

Judge Gray referred to Senator Jim Webb of Virginia who, in looking at the entire criminal justice system in which we hold the world record for the number of people incarcerated, concluded either we are the most evil people in the world or we are doing something seriously wrong.

“There is some evilness behind this,” said Mary Sutton. “White men use drugs at the same rate as black men but aren’t locked up. We have to talk about racism. We have to talk about the caste system.”

If the advances of the civil rights movement have been undermined by the war on drugs, then our path is clear. As Judge Gray concluded, “The most patriotic thing I can do for my country — and I served in the Peace Corps and the Navy — is to work for an end to drug prohibition.”

Diane Lefer is an author, playwright, and activist whose recent book, California Transit, was awarded the Mary McCarthy Prize in Short Fiction. Her stories, novels, and nonfiction often address social issues and draw on such experiences as going to jail for civil disobedience and her volunteer work as a legal assistant/interpreter for immigrants in detention. Her new book, The Blessing Next to the Wound, co-authored with Hector Aristizábal, is a true story of surviving torture and civil war and seeking change through activism and art. Lefer writes for LA Progressive, where this article originally appeared. More about her work can be found at: http://dianelefer.weebly.com/.