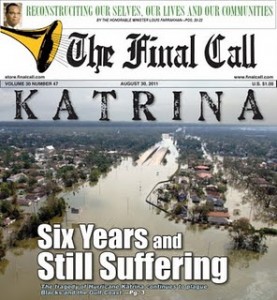

Six Years After Katrina

The Battle for New Orleans Continues

by Jordan Flaherty

As this weekend’s storm has reminded us, hurricanes can be a threat to U.S. cities on the East Coast as well as the Gulf. But the vast changes that have taken  place in New Orleans since Katrina have had little to do with weather, and everything to do with political struggles.

place in New Orleans since Katrina have had little to do with weather, and everything to do with political struggles.

Six years after the federal levees failed and 80 percent of the city was flooded, New Orleans has lost 80,000 jobs and 110,000 residents. It is a whiter and wealthier city, with tourist areas well-maintained while communities like the Lower 9th Ward remain devastated. Beyond the statistics, it is still a much-contested city.

Politics continue to shape how the changes to New Orleans are viewed. For some, the city is a crime scene of corporate profiteering and the mass displacement of African Americans and the working poor; for others it’s an example of bold public-sector reforms, taken in the aftermath of a natural disaster, that have led the way for other cities.

In the wake of Katrina, New Orleans saw the rise of a new class of citizens. They self-identify as YURPs —young urban rebuilding professionals — and they work in architecture, urban planning, education and related fields. While the city was still mostly empty, they spoke of a freedom to experiment, unfettered by the barriers of bureaucratic red tape and public comment. Working with local and national political and business leaders, they made rapid changes in the city’s education system, public housing and nonprofit sector.

Along the way, the face of elected government changed in the city and state. Among the offices that switched from black to white were mayor, police chief, district attorney and representatives on the school board and City Council, both of which switched to white majorities for the first time in a generation. Louisiana also transformed from a state with several statewide elected Democrats to having only one: Senator Mary Landrieu.

While black community leaders have said that the displacement after the storm has robbed African Americans of their civic representation, another narrative has also taken shape. Many in the media and business elite have said that a new political class — which happens to be mostly white — is reshaping the politics of the city into a postracial era.

“Our efforts are changing old ways of thinking,” said Mayor Mitch Landrieu, shortly after he was elected in 2010. After accusing his critics of being stuck in the past, Landrieu — who was the first mayor in modern memory elected with the support of a majority of both black and white voters — added, “We’re going to rediscipline ourselves in this city.”

The changes in the public sector have been widespread. Shortly after the storm, the entire staff of the public school system was fired. Their union, which had been the largest union in the city, ceased to be recognized. With many parents, students and teachers driven out of the city by Katrina and unable to have a say in the decision, the state took over the city’s schools and began shifting them over to charters.

“The reorganization of the public schools has created a separate but unequal tiered system of schools that steers a minority of students, including virtually all of the city’s white students, into a set of selective, higher-performing schools, and most of the city’s students of color into a set of lower-performing schools,” writes lawyer and activist Bill Quigley, in a report prepared with fellow Loyola law professor Davida Finger.

In many ways, the changes in the New Orleans school system, initiated almost six years ago, foreshadowed a battle that has played out more conspicuously this year in Wisconsin, Indiana, New Jersey and other states, where teachers and their unions were assailed by both Republican governors and liberal reformers such as the filmmakers behind Waiting for Superman. Similarly, the battle of New Orleans’ public housing — which was torn down and replaced by new units built in public-private partnerships that house a small percentage of the former residents — prefigured national battles over government’s role in solving problems related to poverty.

The anger at the changes in New Orleans’ black community is palpable. It comes out at City Council meetings, on local black talk-radio station WBOK and in protests. “Since New Orleans was declared a blank slate, we are the social experimental lab of the world,” says Endesha Juakali, a housing-rights activist. However, despite the changes, grassroots resistance continues. “For those of us that lived and are still living the disaster, moving on is not an option,” adds Juakali.

Resistance to the dominant agenda has also led to reform of the city’s criminal-justice system. But this reform is very different from the others, with leadership coming from African-American residents at the grass roots, including those most affected by both crime and policing.

In the aftermath of Katrina, media images famously depicted poor New Orleanians as criminal and dangerous. In fact, at one point it was announced that rescue efforts were put on hold because of the violence. In response, the second-in-charge of the New Orleans Police Department reportedly told officers to shoot looters, and the governor announced that she had given the National Guard orders to shoot to kill.

Over the following days, police shot and killed several civilians. A police sniper shot a young African American named Henry Glover, and other officers took his body and burned it behind a levee. A 45-year-old grandfather, Danny Brumfield Sr., was shot in the back in front of his family outside the New Orleans convention center.

Two black families — the Madisons and the Bartholomews –Â walking across New Orleans’ Danziger Bridge fell under a hail of gunfire from a group of officers. “We had more incidents of police misconduct than civilian misconduct,” says former District Attorney Eddie Jordan, who pursued charges against the officers but had the charges thrown out by a judge. “All these stories of looting, it pales next to what the police did.”

Jordan, who angered many in the political establishment when he brought charges against officers and was forced to resign soon after, was not the only one who failed to bring accountability for the post-Katrina violence. In fact, every check and balance in the city’s criminal-justice system failed. For years, family members of the victims pressured the media, the U.S. Attorney’s office and Eddie Jordan’s replacement in the DA’s office, Leon Cannizzaro. “The media didn’t want to give me the time of day,” says William Tanner, who saw officers take away Glover’s body. “They called me a raving idiot.”

Finally, after more than three years of protests, press conferences and lobbying, the Department of Justice launched aggressive investigations of the Glover, Brumfield and Danziger cases in early 2009. In recent months, three officers were convicted in the Glover killing (although one conviction was overturned), two were convicted of beating a man to death just before the storm, and 10 officers either pleaded guilty or were convicted in the Danziger killing and cover-up. In the Danziger case, the jury found that officers had not only killed two civilians and wounded four, but also engaged in a wide-ranging conspiracy that involved planted evidence, invented witnesses and secret meetings.

The DOJ has at least seven more open investigations into New Orleans police killings and has indicated its plans for more formal oversight of the New Orleans Police Department, as well as the city jail. In this area, New Orleans is also leading the way: In a remarkable change from DOJ policy during the Bush administration, the department is also looking at oversight of police departments in Newark, Denver and Seattle.

In the national struggle against law-enforcement violence, there is much to be learned from the victims of New Orleans police violence, who led a remarkable struggle against a wall of official silence and now have begun to win justice. “This is an opening,” explains New Orleans police accountability activist Malcolm Suber. “We have to push for a much more democratic system of policing in the city.”

In the closing arguments of the Danziger trial, DOJ prosecutor Bobbi Bernstein fought back against the defense claim that the officers were heroes, saying that the family members of those killed deserved the title more. Noting that the official cover-up had “perverted” the system, she said, “The real heroes are the victims who stayed with an imperfect justice system that initially betrayed them.” The jury apparently agreed with her, convicting the officers on all 25 counts.

Jordan Flaherty is a journalist and staffer with the Louisiana Justice Institute. His award-winning reporting from the Gulf Coast has been featured in a range of outlets including the New York Times, Al Jazeera, and Argentina’s Clarin newspaper. He is the author of the book FLOODLINES: Community and Resistance from Katrina to the Jena Six. He can be reached at neworleans@leftturn.org, and more information about Floodlines can be found at floodlines.org. This article originally appeared on The Root, and is reprinted here by permission of the author.