The Blue River Declaration

An Ethic of the Earth

by The Blue River Quorum

A truly adaptive civilization will align its ethics with the ways of the Earth. A civilization that ignores the deep constraints of its world will find itself in  exactly the situation we face now, on the threshold of making the planet inhospitable to humankind and other species. The questions of our time are thus: What is our best current understanding of the nature of the world? What does that understanding tell us about how we might create a concordance between ecological and moral principles, and thus imagine an ethic that is of, rather than against, the Earth?

exactly the situation we face now, on the threshold of making the planet inhospitable to humankind and other species. The questions of our time are thus: What is our best current understanding of the nature of the world? What does that understanding tell us about how we might create a concordance between ecological and moral principles, and thus imagine an ethic that is of, rather than against, the Earth?

What is the world?

In our time, science, religious traditions, Earth’s many cultures, and artistic insights are all converging on a shared understanding of the nature of the world: The Earth is our home. It will always be our only source of shelter, sustenance, and inspiration. There is no other place for us to go.

The Earth is part of the creative unfolding of the universe. From the raw materials of the stars, life sprang forth and radiated into species after species, including human beings. The human species is richly varied, with a multitude of persons, cultures, and histories. We humans are kin to one another and to all the other beings on the planet; we share common ancestors and common substance, and we will share a common fate. Like humans, other beings are not merely commodities or service-providers, but have their own intelligence, agency, and urging toward life.

We live in a world of nested systems. Living things are created and shaped by their relationships to others and to the environment.  No one is merely an isolated ego in a bag of skin, but something more resembling a note in a multidimensional symphony.

The world is dynamic at every scale. By processes that are probabilistic and often unpredictable, the world unfolds into emergent states of being. Our time of song and suffering is one such point in time.  The life systems of the world can be resilient, having the ability to endure through change. But changes create cascades of new events. When small changes build up and cross thresholds, sudden large transformations can occur. Thus the world in its present form — the world we love and inhabit — is contingent.  It may be, or it may cease to be. If the Earth changes in ways that undermine our lives, there is nothing we can do to change it back.

The Earth is finite in its resources and capacities. All its inhabitants live within its limitations and by its rules. And although life on Earth is resilient and robust, rapid irreversible changes and mass extinction events have occurred in the past. As a result of ignoring the Earth’s boundaries, we are on the brink of causing a transformation of the Earth and the sixth great mass extinction.

Our knowledge of the Earth will always be incomplete. But we know that the world is beautiful. Its life forms, unique in the universe, are wonderful in their grandeur and detail. It follows that the world is worthy of reverence, awe, and care.

Who are we humans?

We humans have become who we are through a long process of biological and cultural evolution. As do many other social species, we possess a complex and sometimes contradictory set of possibilities. We are competitive and cooperative, callous and empathetic, destructive and healing, intuitive and rational. Moreover, we are creatures of consciousness, emotion, and imagination, beings through whom the universe has evolved the capacity to celebrate its own beauty and explore its own meaning in the languages of science and story.

We are dependent on the sun and the Earth for everything. Without warmth, air, water, and fellow beings, we would quickly die. At the same time, we are co-creators of the Earth as we know it, shaping with our decisions the future of the places we inhabit, even as our relation to those places shapes us. In this way, we are members of a community of interdependent parts.

Humans are beings who search for meaning. Our beliefs about the origins of the cosmos influence the way we relate to each other, to other living things, and to the habitats we both depend upon and constitute. Sometimes, we experience wonder and awe at the mysteries of the universe, and fall silent in reverence. Yet, as we strive to comprehend the world, we often divide it into hierarchies of value — pure/impure, spiritual/material, human/subhuman. Although we often exclude and exploit those we judge less valuable than ourselves, we yearn for belonging.

We are born to care. From the first moments of our lives, we seek connection. We deeply value loving and being loved. We find comfort in close connection to other people, other species, and to the wild world itself.

We are adaptable and resilient. Our imagination gives us the ability to envision alternative futures and to adapt our behaviors toward their achievement. When we are at our best, we develop cultural systems in which we, other living beings, and ecosystems can flourish.

We are moral beings. We have the capacity to reason about what is better and worse, just and unjust, worthy and demeaning, and we have the capacity to act in ways that are better, more just, more worthy, more beautiful.

Because we are these things, we can change. Because we are these things, change will be difficult.

How, then, shall we live?

Humanity is called to imagine an ethic that not only acknowledges, but emulates, the ways by which life thrives on Earth. How do we act, when we truly understand that we live in complete dependence on an Earth that is interconnected, interdependent, finite, and resilient?

Given that life on Earth is interconnected, we are called to affirm that all flourishing is mutual, and that damage to the part entails damage to the whole. Accordingly, our virtues are cooperation, respect, prudence, foresight, and justice. We have the responsibility to honor our obligations to future generations of all beings, and take their interests into account when we reflect on the consequences of our actions. To discount the future, to take all we need for our own well-being and leave nothing for others, is unthinkable. We should take only what the Earth offers, and leave as much and as good as we take. To live by a principle of reciprocity, giving as we receive, re-creates the richness of life, even as we partake of it. Then, our harvests are respectful and thoughtful. We learn to listen, which means that we learn to value congeniality, patience, fairness, and moral courage, which creates the possibility of heroism in the face of disagreement and discord. Moreover, the new ethic calls us to remedy destructive distributions of wealth and power. It is wrong when some are made to bear the risks of the recklessness of others, or assume the burden of others’ privilege, or pay with their health and hopes the real costs of destructive practices.

Given that humanity is inescapably dependent on the Earth for gifts both material and spiritual, we are called to be grateful and humble. To be grateful is to express joy for the fertility of the Earth, to be attentive to its gifts, to celebrate its bounty, and to accept responsibility for its care. Humility is based on an understanding of our own roots in the soil; we recognize the danger we face and the damage we do when we get that wrong. So we are well-advised to be humble about our claims to knowledge; and with art and heart and science, to strive for continuous learning that is open to evidence from all ways of knowing and from the Earth itself. The generosity of the Earth models generosity in our relations with others, and calls for collective outrage when we fail in that duty. A new ethic calls us to defend and nurture the regenerative potential of the Earth, to return Earth’s generosity with our own healing gifts of mind, body, emotion, and spirit. We can find joy and justice in sustaining lives that sustain our own.

Given that the Earth’s resources and resilience are finite, human flourishing depends on embracing a new ethic of self-restraint to replace a destructive ethos of excess. Greed is not a virtue; rather, the endless and pointless accumulation of wealth is a social pathology and a terrible mistake, with destructive social, spiritual, and ecological consequences. Limitless economic growth as a measure of human well-being is inconsistent with the continuity of life on Earth. It should be replaced by an economics of regeneration. Simple life styles that include thriftiness, beauty, community, and sharing are pathways to happiness. Celebrated virtues are generosity and resourcefulness.

Given that life on Earth is resilient, humanity can take courage in Earth’s power to heal. We can find guidance in the richness of diverse cultures and ecosystems, if we honor and protect difference. Equality and justice are necessary conditions for civilizations that endure, and truth-telling has strong regenerative power. Virtues we can embody are human courage, creative imagination, and perseverance in the face of long odds. The effect of humans on the land can be healing; our obligation is to imagine into existence new ways to live that create resilient and robust habitats. If we can undo some of the damage we have done, this is the best work available to us. On the other hand, damaging the natural sources of resilience — degrading oceans, atmosphere, soil, biodiversity — is both foolhardy and an offense against the future, not worthy of us as rational and moral beings. If hope fails us, the moral abdication of despair is not an alternative. Beyond hope we can inhabit the wide moral ground of personal integrity, matching our actions to our moral convictions. Through conscientious decisions, we can refuse to be made into instruments of destruction. We can make our lives and our communities into works of art that express our deepest values.

The necessity of achieving a concordance between ecological and moral principles, and the new ethic born of this necessity, calls into question far more than we might think. It calls us to question our current capitalist economic systems, our educational systems, our food production systems, our systems of land use and ownership. It calls us to re-examine what it means to be happy, and what it means to be smart. This will not be easy. But new futures are continuously being imagined and tested, resulting in new social and ecological possibilities. This questioning will release the power and beauty of the human imagination to create more collaborative economies, more mindful ways of living, more deeply felt arts, and more inclusive processes that acknowledge the ways of life of all beings. In this sheltering home, we can begin to restore both the natural world and the human spirit.

November 2011, The Blue River Quorum

Meeting in the ancient forests of the Blue River watershed in Oregon, the Blue River Quorum includes J. Baird Callicott, Madeline Cantwell, Alison Hawthorne Deming, Kristie Dotson, Charles Goodrich, Patricia Hasbach, Jennifer Michael Hecht, Robin Wall Kimmerer, Katie McShane, Kathleen Dean Moore, Nalini Nadkarni, Michael P. Nelson, Harmony Paulsen, Devon G. Pena, Libby Roderick, Kim Stanley Robinson, Fred Swanson, Bron Taylor, Allen Thompson, Kyle Powys Whyte, Priscilla Solis Ybarra, Gretel Van Wieren, and Jan Zwicky. The Quorum was convened by the Spring Creek Project for Ideas, Nature, and the Written Word (springcreek@oregonstate.edu) with funding from the Shotpouch Foundation, the Oregon Council for the Humanities, and the USDA Forest Service.

I read the declaration. I am in total agreement with the goals and the principles outlined. What we need now is to begin connecting communities of people who are concerned. These communities need not be created, they are there. Doing other things but who can connect to others through sharing information putting together a plan that can mobilize us to speak out against the horrible events that occur in so many ways, such as trafficking, anti-immigration politics, the continuing racism and sexism and homophobia, and the destruction of self determination of communities that want to tend to the education and health of their residents. Thank you for sharing.

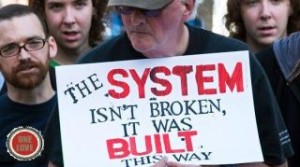

1As an American Indian scholar, I was pleased to see such consistency with traditional Indigenous values and assumptions about the world. I support this declaration, although I feel it is always good to recognize that many living cultures have lived according to these values for thousands of years. The “system that was built this way” is a relatively recent produce of a different set of cultural values. With such recognition, not only can we re-confirm our ability to re-member this way of being in the world, but rather than continue to destroy the wisdom holders of many aspects of this way of thinking and surviving that I’m sure the quorum members have largely forgotten.

2Signed, Four Arrows

Unlearning the Language of Conquest; Critical Neurophilosophy and Indigenous Wisdom; Primal Awareness et al

In lak ech, Four Arrows.

I find myself agreeing with your new work with Greg Cajete & Jongmin Lee, Critical Neurophilosophy and Indigenous Wisdom. Please read my earlier post here on learning nonviolence and peacefulness, as well as conviviality, from Zapotec child-rearing customs and practices.

I am working on a response to your first chapter, and your unique critique of the ultimatum game; my approach is based on an entirely different set of concepts about indigenous and alterNative subjectivity and derived from mutual reliance interests as biocultural meme.

3I look forward to hearing from you and learning about your work and alterNative subjectivity ideas. Feel free to email me at djacobs@fielding.edu

4This is beautiful. At the same time, a few of us have been saying these same things for forty years and working to make change, to create new ways of being, to remember old ways…only to see America in the grip of virulent racism and obscene economic inequality. How will all of us not only write and speak these beliefs, but live them? I’d love to read responses from people.

5I am most interested in tearing apart the media (whether mainstream or progressive) constant use of “we” as though the term spoke for all races, ethnicities, ages, income levels and genders.