Signs of the Times

Reflections on a Society in Turmoil

by Randall Amster

Today we are confronted with a convergence of crises that is unparalleled in recent memory. Overtly discriminatory policies, the elevation of oppressive ideologies, ignorance and disregard as  political virtues — these are among the hallmarks of this moment. As outrageous as this is, it is also important to remember that none of this exists in a vacuum, and that to some extent these patterns have been with us in various forms for a long time. In considering the cultural context for navigating contemporary challenges, I am drawn to recollections from not long ago…

political virtues — these are among the hallmarks of this moment. As outrageous as this is, it is also important to remember that none of this exists in a vacuum, and that to some extent these patterns have been with us in various forms for a long time. In considering the cultural context for navigating contemporary challenges, I am drawn to recollections from not long ago…

Exiting a natural foods store in the southwest a few years ago, I noticed a person flying a sign on the side of the road. It was apparently a young woman, complete with piercings and other hallmarks of the disheveled look that is sometimes known as “crusty†or “gutter punk†in many cities. What stood out for me, indelibly in this case (in addition to the feelings I experience any time I see someone asking for help in such a manner) was the language on her sign, composed of three words in all: Broke. Hungry. Ugly.

It was the last one that really got me. I stopped to give her the change I had received from the store, and she replied with an uncomfortable thank you. She was not in fact ugly, but one could almost sense in her demeanor that she believed that she was. Aesthetics aside, it was also apparent how standing with a sign like that could make her especially vulnerable to all sorts of exploitation, giving cause to wonder what had transpired in her life previously to lead her to that point in time to that median with that sign.

No, she was not ugly — but a society that allows such forms of marginalization and self-loathing among its youth isn’t particularly all that easy on the eyes. Obviously the 80 cents in change that I handed her didn’t come close to remediating any of this, and it’s also worth noting that few people even stopped to interact with her at all. Culturally, we don’t do well with public displays of dysfunction or desperation, preferring instead that people keep their problems and shortcomings at home where they belong.

In the case of those lacking a home, as well as those who are precariously homed in tenuous conditions, there is no such private space to adequately contain one’s travails. A young woman with a sign like that, being largely ignored in broad daylight, is not merely an individual call for help. It’s a reflection of our collective indifference, our hardened cynicism, our revulsion at our own vulnerability. We don’t want to be reminded of such things — not because they’re alien, but maybe because they cut too close to home.

And this brings us nearer to the crux of the matter: what does it mean to be “at home†and who is entitled to enjoy the benefits of being there? It’s possible (as is the case with many street youth) that the young woman with the sign had fled from a home life that was abusive or intolerable. She might experience more of a sense of “home†living on the streets with other young people in similar situations. She may even have an aversion to a fixed abode as being stagnant or otherwise rife with regimentation.

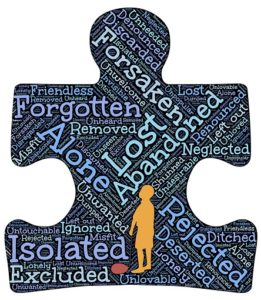

Explanations of this sort are not uncommon on the streets, especially among homeless youth. You might imagine that there must be adequate services available to help young people cope with such issues, and assume that those like the young woman with the sign must be “service resistant†or somehow beyond help. In reality there are insufficient resources in most locales — and more to the point, how exactly does a society meaningfully address widespread experiences of alienation, vulnerability, and marginalization? Fanning the flames of “otherness†and targeting certain groups of people clearly isn’t a viable response.

Indeed, the young woman with the sign is probably more like us than we would want to acknowledge; in this light, we might surmise that she was holding up a mirror and not merely a cardboard sign. Consider how many of us with jobs and homes are essentially broke, extending our access to credit to cover necessities and carrying debts beyond our assets. Consider further how many of us are perpetually hungry, continually filling our bodies with processed foods of dubious nutritional value. Or consider how many of us may feel ugly — as in: inadequate, misunderstood, underappreciated, or otherwise wanting.

Broke. Hungry. Ugly. This is a social commentary and not merely a personal plea. A society defined by gross wealth inequality and pervasive precarity, built on a foundation of adulterants and artificial ingredients, and unwilling to look these issues squarely in the eye really is not a pretty picture at all. This may have been on a placard observed in the recent past, but it remains a troubling sign of the times right now.

Randall Amster, J.D., Ph.D., is Director of the Program on Justice and Peace at Georgetown University, and is the author of books including Peace Ecology.

Powerful commentary, Randall. Yes. Lately I have felt like I am no longer “at home” in my own country, a sense of unease that I have been wanting to interrogate more deeply. The overt reasons leap from each day’s headlines. But, as the Talking Heads song goes, “How did we get here?”

One place we are all at home: the natural world, our Mother Earth. We’d do well to remember this, another way of “thinking globally, acting locally.”

1