Will We Ever Learn?

High-Stakes Testing Undermines the Essence of Teaching

by Robert C. Koehler

A mind is a terrible thing to test, especially a child’s mind — if, in so doing, you reduce it to a number and proceed to worship that number, ignoring the extraordinary complexity and near-infinite potential of what you have just tested.

“In every work of genius we recognize our own rejected thoughts: they come back to us with a certain alienated majesty.â€Â What if?

“In every work of genius we recognize our own rejected thoughts: they come back to us with a certain alienated majesty.â€Â What if?

What if the American education bureaucracy understood these words of Ralph Waldo Emerson and honored the latent genius of every student? What if it funded teachers and schools with as much enthusiasm as it did corporate vendors? What if, in some official way, we loved kids and their potential more than the job slots we envisioned for them and judged them only in relationship to their realization of that potential? What if standardized testing, especially the obsessive, punitive form that has evolved in this country, went the way of the dunce cap and the stool in the corner?

What if the education process were allowed to move the human race to a higher level of awareness? That is to say, what if it weren’t stagnant and political but, instead . . . sacred, in the way that it feels sacred to hold an infant in one’s arms?

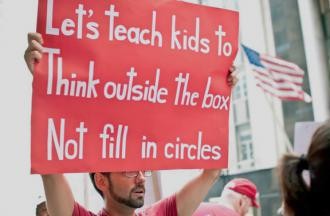

I know that’s asking a lot, but I feel emboldened to pose such questions as I become aware that standardized testing and the all-pervasive political hold it has on education is being challenged at the grass-roots level. Teachers across the country are standing up to the standardized testing system and parents are opting out of it: They’re refusing to let their 8- to -13-year-olds take these “high stakes†tests that so many jobs and so much money rides on. And this movement, small as it is, has become news.

The Riverhead (N.Y.) News-Review, for instance, reported last week that “parents and educators statewide continue to protest so-called high-stakes testing tied to the controversial Common Core State Standards,†with the parents of 118 students in grades 3 through 8, in the Shoreham-Wading River school district, on Long Island, saying “their children will not sit†for the English and math tests in April and May, up from 25 who opted out last year.

And Gina Bellafante, writing recently in the New York Times, noted: “The most significant aspect of this wave of testing dissent is its expansion beyond the world of affluent white parents and celebrated schools, where children are largely destined to succeed. On Thursday, parents in Harlem gathered to announce their displeasure with a system that has forsaken meaningful education for a culture of obsessive examination. More than 100 families at Hamilton Heights School, an elementary school where 80 percent of students receive free lunch, had sent letters alerting the principal that their children would decline to take the tests.â€

What’s so wrong with standardized testing that a movement is rising up against it? A number of complaints come up again and again. The most egregious and overwhelming, from my point of view, is that such testing fails to measure what it claims to measure, often by a long shot, but nevertheless inevitably produces scores gauging the knowledge level of every student taking it, which, when below preset standards, are used in a punitive fashion against both teacher and school, denying them jobs and funding.

Furthermore, a great deal of time and effort go into the preparation for and administration of the tests, thus stealing time from other subjects — even in classes where the students aren’t being tested. One mother, for instance, quoted in a report on Pittsburgh TV station WTAE said that her daughter, a first-grader, “may be too young to take the tests, but she’s losing class time because her teachers are helping to administer them to other students.†Inevitably what disappears from classrooms is focus on the arts and other “soft†subjects, mastery of which, of course, hardly lends itself to simplistic measurement.

Many parents complain about the stress their kids are placed under to participate in these high-stakes tests, which play such a role in the fate of teacher, school and district: absurd, joy-choking stress it hardly makes sense to require young children to endure. Added to that is a fear of test-taking that many students already have, which high-stakes testing only aggravates. Such factors throw the validity of the statistics the tests produce into serious question.

Other factors also sully these stats, which have such power to wreak havoc in our schools. From the website Change the Stakes: “State exams are loaded with poorly written, ambiguous questions. A recent statement signed by 545 New York State principals noted that many teachers and principals could not agree on the correct answers.â€

Diane Ravitch makes the point that the tests give no useful feedback to teachers about what the students actually know. “They have no diagnostic value,†she writes on her website. “The test asks questions that may cover concepts that were never introduced in class. The test is multiple-choice, creating an unrealistic expectation that all questions have only one right answer.â€

And, eerily: “High-stakes testing undermines teacher collaboration,†the Change the Stakes website points out. “Teachers are judged on a curve, which discourages them from helping students in another teacher’s class.â€

The simplest, most plaintive complaint of all is that these tests take the joy out of learning. They mock the craft and complexity of teaching at the same time that they hold schools and teachers responsible for all the unaddressed socioeconomic impediments to learning that plague our society. In the movement to counter standardized testing, the stakes are high indeed.

Robert C. Koehler is an award-winning, Chicago-based journalist and nationally syndicated writer, and a Contributing Author for New Clear Vision. His new book, Courage Grows Strong at the Wound (Xenos Press) is now available. Contact him at koehlercw@gmail.com, visit his website at commonwonders.com, or listen to him at Voices of Peace radio.

National Education: a critique.

Education services across the globe at present, are designed to serve the interests of the national governments, rather than those of the pupils. Of course, it is assumed that these interests are the same. A large number of governments, including England, France, Italy,Spain, Greece, Ireland,Hungary, Austria, Poland, Japan, India, Saudi Arabia, Syria, Iran, Jordan, Algeria, Egypt, Turkey, enforce National Curricula, devised by government departments,and designed to control what is taught; how? to whom? by whom? and how assessed?

In general the provision and supervision of education services are centralized and controlled by governments: National Education.

It is not devolved to communities. It is worth noting that knowledge is seen as a commodity: as sets of facts that can be transmitted to pupils and students in schools and colleges. In their turn, teachers and trainers, as qualified experts, do not question the validity, nor the veridicality, of the knowledge that they are transmitting. The organizers of the National Curriculum only express doubts about what is to be included in their prescriptions, never about the validity of the prescribed knowledge. Such knowledge is divided into subjects, and the teachers are trained, qualified and certified to teach their subjects, and the students tested to the required subject standards. The developers of a National Curriculum assume that education is teaching: and that knowledge is to be taught by transmission, by instruction; and the pupils learn by rote. The assumption that Education is teaching’ accepts that knowledge is derived from the testimony and evidence of others. Administrators, teachers and trainers identify what is to be taught, and adopt methods to teach efficiently and effectively the authorised knowledge to the learners. What is to be taught is defined by agents and agencies in society. The transmission of the content of a National Curriculum leaves little room for any negotiation and assumes that there is agreement. Curriculum content is fixed and relatively static. The National Curriculum, as practiced by many governments, with its emphasis on prescribed content and testing, has encouraged the use of didactic teaching methods to ensure that the approved content is transmitted. In such systems, to be ‘educated’ is to ‘absorb and practice’ what is taught and involves the transmission of knowledge from an expert to a novice; an adult to a child; a teacher to the taught; the teacher knows the knowledge and truth which the pupil has to learn. This model is hierarchical, placing the learner as subordinate to the teacher: the teachers as the authority in the school or college, and the officers of governments as the rulers of the teachers, telling them what to teach. In such a National Curriculum, it is taken for granted that education is teaching. It takes place only in authorised schools within formal settings, and involves the teaching of knowledge, often described as the truth, and always approved and authorised.

Education is seen as development, as betterment, as progress, with purposes that are specified by the government, and direction overseen by authorities that define what is normal, and permissible. Education services must be seen as the responsibility of agencies of the governments, or religious authorities, prescribing what happens in their schools. In many countries education services are determined by politicians not educators nor communities. For example, in the UK, during 1986, Prime Minister Thatcher asserted that education was too important to be left to the teachers. She directed Kenneth Baker, the Secretary of State for Education, to develop an Education Act in which the teachers became agents of the government, doing as they were told, according to a National Curriculum for all schools and colleges in the public sector, declaring that this was the way to raise standards and create an effective education service to enable Britain to compete in the 21st century. This Act specified the ages that children started the different schools, how many hours the teachers are to work, the aims and objectives of the educational programmes, the content of textbooks, the targets, standards, and the assessments of the pupils and the teachers. The focus would be on the attainment of specific standards for all children at specified ages. In any one school all the pupils were expected to reach those standards judged correct for their age group. If they did not, the school would be judged to have ‘failed’. Course material was prepared by central agencies and made available to the teachers, with recommendations about the delivery of the lessons.

Paolo Friere, and Ivan Illich, declared that education has to be about learning communities, involving everybody, young and old, in the processes of learning new knowledge, skills, and attitudes. A closed, didactic prescriptive system, such as a national curriculum, is not adequate to these objectives. An alternative education is to move towards an open, process-based, negotiated curriculum which is based upon general learning outcomes, key skills and collaboration and participation. This involves a change from seeing education as teaching to seeing education as learning.

Education as learning

Education as Dialogue

Education as Problem solving

Education as negotiated curricula

Education as Liberation

Education as Virtual Learning

Education as Green Living

It is not based on selection, streaming and meritocracy. Alternative models emerge which are based on mixed ability, topic-based curriculum approaches in which the teacher, the learner and the community identify what is to be learned. These strategies are based on a respect for diversity; a recognition of our interdependence; that learners are in cooperation not competition; and that we are all learners. In fact, learning is living and takes place everywhere. In case you think that these ideas are ‘too modern’, it is worth reminding ourselves that they were also developed in the USA [1900 – 1950] by John Dewey, who held that we learn through experience, by doing, and argued that greater emphasis should be placed on problem solving and critical thinking skills. Dewey emphasised that ‘teaching’ is too concerned with the delivery of knowledge. This needs to be balanced by a much greater concern with the students’ actual experiences, and active learning. He was an exponent of ‘experiential education’ based on project based learning, with the learners as active researchers.

The work of Bruner confirmed that the learner is active. Whereas ‘Teaching’ assumes that ‘learners’ are passive…..doing as they are told! Bruner emphasized that learning is a social process.

Learning is an active, social process in which students construct new ideas or concepts based on their current knowledge. The student selects the information, forms hypotheses and then integrates this new material into their own existing knowledge and mental constructs. This is a continual process.

Learning occurs in three stages: Enactive – in which children need to experience the concrete (manipulating objects in their hands, touching a real dog) in order to understand. Iconic – students are able to represent materials graphically or mentally (they can do basic addition problems in their heads). Symbolic – students are able to use logic, higher order thinking skills and symbol systems, and understand statements like ‘too many cooks spoil the broth’. (Educational Psychology 1998)

How are skills and knowledge acquired? These things are not acquired gradually, but more in a staircase pattern which consists of spurts and rests. Spurts are caused by certain concepts clicking, being understood. These have to be mastered before others are acquired, before there is movement to the next step. These steps are not linked to age but more toward environment. Environments can slow down the sequence or speed it up. [Journal of Social Issues 1983] Bruner felt that knowledge was best acquired when students were allowed to discover it on their own.(Milner,1991].’Learning as discovery’, arising from active social processes, will talk about learning spaces, not teaching rooms. These spaces can be in the field, forest, street, museum and classroom. The learners will not be organized in rows but in flexible patterns. Sometimes all age groups will be together, other times friends, and family groups. The knowledge is not prescribed, it is to be discovered. The teacher is not at a high desk at the front of the room, but is sitting with the learners: sometimes the learner, the leader, the adviser. Lessons are not a series of prescriptions, but a complex series of problems to be solved jointly. For those with access, the library is the world wide web with up-to-the minute information, facts, statistics. For others, the creative use of the local community and neighborhood can provide personal experiences and local knowledge from which to encourage investigation, and an innovative database.

The communities of learners are actively involved in negotiating their studies with teachers who see their role as co-learners, organizing and structuring the learning experiences. This means that the teachers must themselves become learners, developing their skills in planning the presentation of problems and devising a supportive structure to guide learners in their explorations.

The debates about learning as discovery or instruction have been going on for a long time.

1Confucius [450BC] stated

Tell me and I will forget.

Show me and I may remember.

Involve me and I will understand.